Quantifying B.U.F. Propaganda

A brief summary of findings from analysis of 'Blackshirt', 'Action', and 'Fascist Week'

On this page I am going to set out a record of the data I have collected from the publications of the British Union of Fascists. Whilst I would like to make it into a full essay, I am going to try to stick to just the data and some brief explanations - a full write-up would both make this article exponentially longer, and risk self-plaigarism. Much of the data here I could not utilise very much in my essay on the topic, but I hope by posting it here, it will be of at least some interest.

Background

The British Union of Fascists (BUF)

I am not going to give a history of the BUF. If you would like one, there is an open-access essay at the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, by Julie Gottlieb. You can also read a more brief albeit somewhat irritating rundown of Mosley from the BBC. I will, however, highlight a few key events to clarify some parts of this article.

From January to July in 1934, the BUF was supported by Viscount Rothermere, who owned the Daily Mail and Daily Mirror. This, and a moderation in rhetoric, attracted middle-class and even some Jewish members. A chaotic meeting in June, at Olympia, shattered the BUF’s reputation and led to Rothermere dropping the sponsorship.

In 1936, the BUF attempted to march through Whitechapel in the East End of London to antagonise the Jewish population there; they were met with heavy resistance in what became known as the Battle of Cable Street. Cable Street as a great turning point in BUF history is a myth; the BUF saw an increase in support as they looked to the 1937 London elections. Oliver Kamm briefly covers the topic here but it is worth reading Daniel Tilles’ article if you can.

Beset by factional disputes, and being repressed by the government, the party became increasingly marginalised. After a campaign for peace with Germany, it was finally banned in 1940, its leaders imprisoned.

The Newspapers

The three main BUF newspapers are represented here;

[The] Fascist Week, a short-lived paper aimed at fascist sympathisers. It was incorporated into Blackshirt.

[The] Blackshirt, the BUF’s longest lived newspaper. It targeted party members but was also the main paper of the BUF until 1936, before becoming a pure house journal.

Action, which briefly acted as the paper of Mosley’s proto-fascist New Party, before being revived in 1936 as the main paper of the BUF.

Note that reliance on the British Online Archives means that a few issues are incomplete or missing.1

A Brief Note on OCR

Or, A̟̱̞̟̍ͩͬ͋͘ 6rief note an (964

I was initially going to write a full explanation of Optical Character Recognition (OCR) and how it was used here, but it started to drag on. I will go into more depth in a later post, maybe. To put it briefly; a lot of OCR output is worthless gibberish that ends up being obscured by search engines to make it appear useful. This has a severe impact on the humanities. That does not mean we should give up, however, but instead be more thoughtful with how we use it.

At the time, the OCR provided by the British Online Archives was not sufficient (to their credit, it appears to have changed since then). Adobe Acrobat provided some passable character recognition, but working with it was difficult and it was poor at recognising segments (columns, caption boxes, etc.). I spent about a week training ABBYY Finereader to recognise the newspapers and process them, which turned out to be a complete waste of time. I will give a quick comparison of the results of scanning the image below.

OCR Output Comparison

ABBYY2

Had it not been for such gross proliteering, the Government would not have to foot the biII that has led to a severe and unjustitiable cur-tailment of social Services in Surrcy and elsewhcrc, which samc restriction is producing an ever strongcr body of resentment that should cjusc ottr adniinistrators to think twice over the degree of free-dont they allow those now happily lining pockcts at the national expense.

Adobe

Had it not been for such

important as the three fightof roads, education, housing, waiting for that leadership has led to economics in the gross profiteering, the Gov

police and many other services which is a crying need. We shape of slowing up or cuternment would not have to

ing services, which are made must hope and pray that it

which should be national fall ting down the programme for foot the bill that has led to a[…]

Tesseract-OCR

Had it not been for such gross profiteering, the Government would not have to foot the bill that has led to a severe and unjustifiable curtailment of social services in Surrey and elsewhere, which same restriction is producing an eyer stronger body of resentment that should cause our administrators to think twice over the degree of freedom they allow those now happily lining pockets at the national expense.You can see why I chose Tesseract. It’s far from perfect, but when you have a free piece of software that can outdo software costing hundreds of pounds - in the space of a few minutes - you know which way to go. After scanning I did have to run the text through the proprietary software Afterscan.

Results

The BUF and the Jews

Harsh things were said, and harsh things done… But I was not before that, and I have not been since - and even at time - was not antisemitic.

Oswald Mosley, 1975, in an interview for Thames Television.

This war is no quarrel of the British people; this war is a quarrel of Jewish finance.

Oswald Mosley, 1st September 1939.

Regarding Methodology

In his fantastic work British Fascist Antisemitism and Jewish Responses, 1932-40, Daniel Tilles carries out a manual study of BUF publications and their antisemitism, in far more depth and quality than any other author. But it is worth noting a few limitations to this approach. Tilles has to take the decision to limit his sample size to every first and third issue of the month, missing several important articles. More significantly however is Tille’s decision to limit his analysis, up until 1937, to only the first four pages of every issue. The letters to the editor, ‘The Jews Again,’ later known as the ‘Jolly Judah’ column, and reports local affairs (important during the East End campaigns) are all missed out.

Patterns of Antisemitism

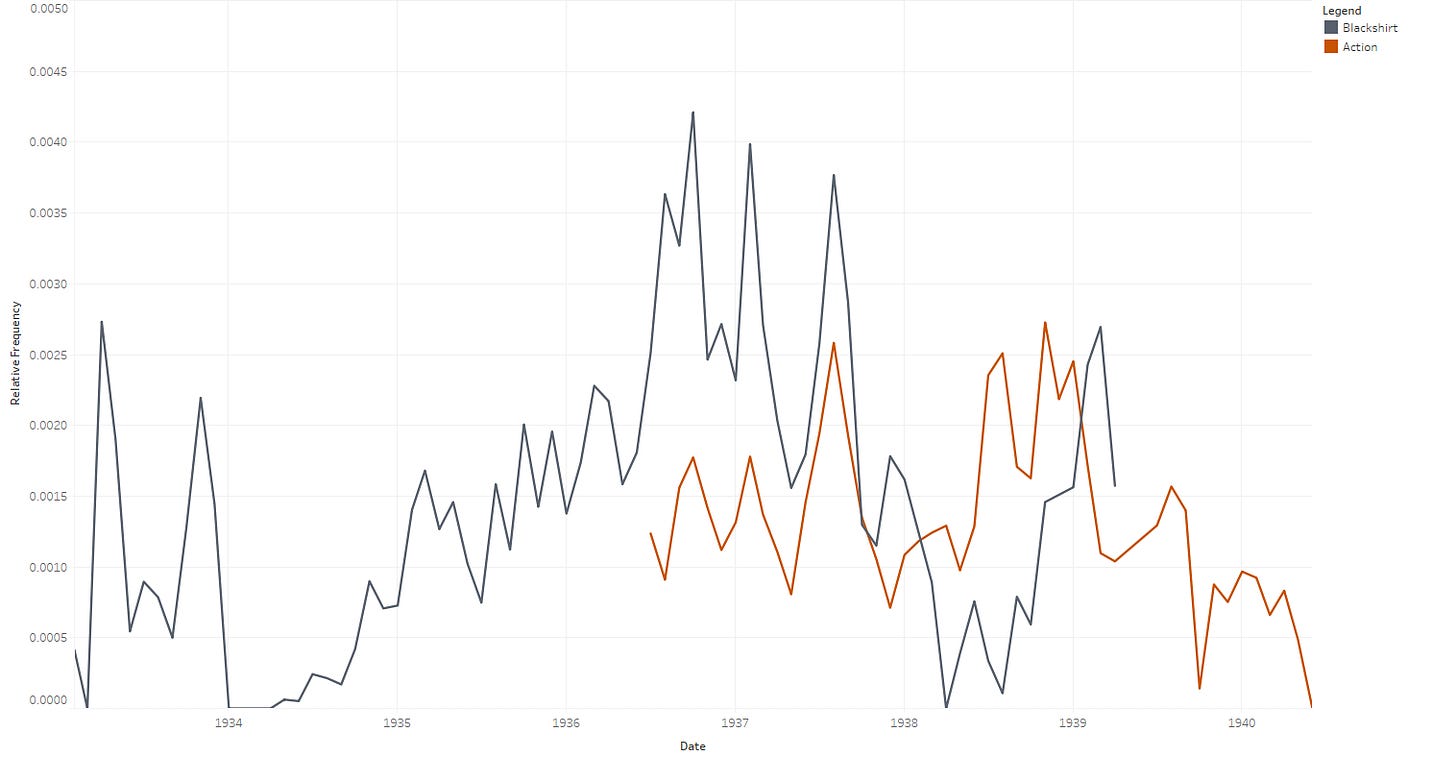

We can get a general idea of BUF antisemitism simply by examining how much they were discussing Jews.

Of course, not all discussion of Jews was necessarily antisemitic. In particular, early articles - most notably, the headline ‘Fascism and the Jews’ - sought to set out an ‘inclusive’ fascism that distanced itself from Nazi persecution. But as we can tell from Tilles’ earlier research, these were increasingly rare and, in his words, ‘unambiguously positive sentiment was never expressed’. By the end of the Rothermere period every article mentioning Jews was doing so in an explicitly negative light.

The extent of Rothermere’s influence on the BUF is revealed by the vanishing of Jews from the pages of Blackshirt and Fascist Week during his sponsorship. We also see a slight perseverance in ‘codewords’ for Jews. Mosley’s insistence that he could not control the levels of antisemitism within the papers seems weakened.

Scapegoats

The original (one might say OG) scapegoat for the BUF was the ‘Old Gang’. This term signified the older politicians who ran British society and had ‘betrayed’ the Lost Generation during the war. The Old Gang was a popular scapegoat for Mosley’s New Party, and carried over when he formed the BUF.

Robert Benewick credits Captain C. C. Lewis, editor of Blackshirt, for employing the term during his tenure. He left the paper at some point between the end of 1933 and February 1934, and the decline around that time makes the theory - that he was the chief proponent of it - appear more plausible.

After the Rothermere period it was Jews who would emerge as the scapegoat of choice, and the Old Gang were only mentioned in passing.

The ‘Decline’ of Fascism

What is evident from the papers is the decline of fascism as a self-descriptor and the brief rise of national socialism. This is exemplified in the removal of the fasces and adoption of the flash and circle in 1935; an attempt to adopt a ‘British swastika’.

Indeed, before 1936, the term ‘National Socialist’ (or -ism) barely appears at all in the pages of Blackshirt.

We can see four distinct phases in these data;

1933-1934: A period of introduction for the many new readers, touting the benefits of fascism and attempting to prevent the term being seized by rivals.

1934-1936: Consolidation after a decline in new sign-ups and the scandal of Olympia.

1936-1938: A switch from Roman to Teutonic fascism (see below).

1938-1940: Apathy, focus on anti-war campaigns and outward criticism rather than promotion of ideals.

The switch from Roman – i.e. Italian, to ‘Teutonic’ – i.e. German fascism, over the course of the 1930s, has been proposed by historians (notably Claudia Baldoli) as secret files relating to Mosley’s dealings have been released. As the party struggled to grow, it is hypothesised that Mosley became financially dependent on Hitler and Mussolini. The Italians withdrew support at some point in 1937, and in June of that year, Goebbels noted in his diary that ‘Mosley needs money’. Stephen Dorril estimates he received about £50,000, roughly equivalent to £2.5m today.

Robert Benewick also notes the switch, although he emphasises the relation to Germany’s overtaking of Italy as the primary fascist power in Europe. A certain intellectual ennui and frustration also began affecting the party as their support dwindled. Fascism was no longer an exciting word; ‘[t]he BUF had lost its novelty or curiosity value’, he writes.

Pledges

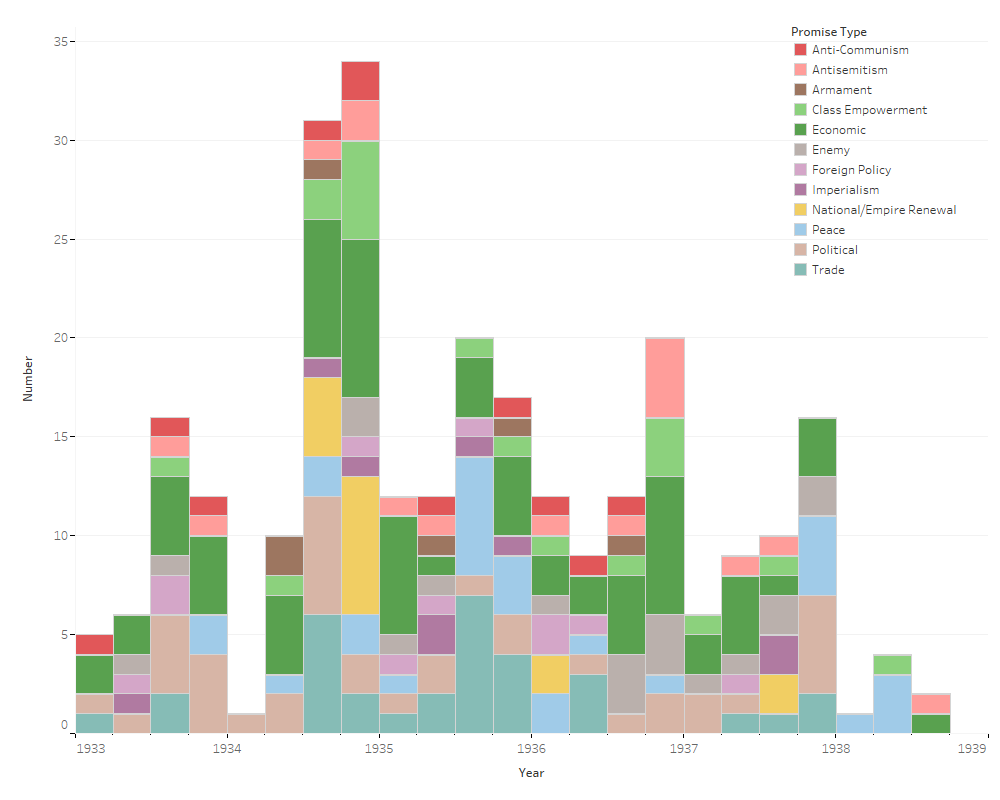

‘Pledge studies’ has existed in political science since the 1960s (for example, see this 2013 collection of studies into British politics, which contains many fascinating looks at the art of the political promise).

On a basic level this can simply involve recording every instance of the phrases ‘we will’, ‘we shall’, ‘I will’, etc., and then filtering them appropriately.

There are several interesting results here; the vanishing of armament promises as the crisis in Europe emerges, the decline of anticommunism, and the sporadic rhetoric around national and imperial renewal all warrant further investigation.

This was not the focus of my study, but I would be interested in exploring this further in the future.

Geography

Currently, I only have the georeferenced data for 1933, as extracting and visualising it is resource-intensive. I will however quickly go over these data, as this is an area that particually interests me. I hope to produce more in the future.

Have we just reproduced a population map? Not quite. Here, by the way, is a population map from around the same time (1931).

There is less density in Scotland - and yet, a substantial presence in the cities of Glasgow and Edinburgh. It seems odd that the latter seems more popular, despite the former having a large Jewish population. The BUF in Scotland is a contentious topic - I’m not sure at the moment I can bring much clarity to the debate.

Another oddity to note is the lack of interest in Northern Ireland. Mosley and the BUF’s complicated relation with Ireland certainly did themselves no favours in gaining traction here, and there was certainly only limited benefit for them to gain here. That is not to say that fascism was alien to Northern (or the rest of) Ireland, but the BUF preferred to focus on the mainland.

Ending Remarks

I intend to carry out further analysis, which I will upload here when I can. At some point in the future, when I am at liberty to do so, I would like to publish something far more substantial. That said, these results themselves already challenge some assumptions about the BUF I have observed from historians. I hope they are at least mildly interesting.

Interestingly, the collection has passed through several hands. The papers were apparently accrued by Robert Saunders, district leader of the BUF for Dorset West, later a founding member of the post-war Union Movement and Constituency Organiser for Wessex. After his death it was passed to Jeffrey Wallder, member of the remnant Friends of Oswald Mosley group, who has often awkwardly collaborated with historians of the subject. At some point passing through both the University of Birmingham’s Cadbury Research Library and the National Archives, it was digitised by the British Online Archives in 2018.

This is a generous example. The OCR generated for the headline and first sentence was;

:i ARMAMENTS

HIT SURREY

11

>r N ll-EASCISTS quote

“ guns not butter ” is * • ns a slogan to show ,t rearmnment at the coM of it hardship is being enforccd under National Socialism abroad.